Kthaahthikha

30 June, 2005

The Hunt - I. The Borderlands.

Alef reined her scuttler in at the tip of the rise. It was a hot, muggy, overcast day, and the promise of a storm before nightfall did little to lighten her disposition. The boiler began to rumble, so she kicked the valve, a jet of hot steam condensing and covering her in a wash of warm water.

Down below the rise, the plains began once more in earnest. Binoculars showed a small encampment on the horizon, but she couldn't make-out the tribe and, to be frank, she didn't really care.

The boiler began to rumble again. Alef contemplated stopping for lunch, deciding in favour of a snack in the chair. She cranked the motivator and steamed flooded into the pistons, setting the scuttler down the earthen bank and loping on its matte-camo legs. She swiveled back and forth on the saddle, maintaining a balance. As she did so she fetched a sandwich from the travel compartment with one hand, and unslung her rifle with the other.

She had two magazines full of mercury rounds, two full of hollow-points, and one of steel tips. She shoved the sandwich in her mouth and loaded the hollow-points. Realistically, they'd be the ones most needed.

Around mid-afternoon, with the first rumbles of thunder coming down from the north, twelve Ispahat dragoons came riding out of the encampment. They were mounted on thierets and mostly armed with scatter-bows and javelins. Just in case anyone ever made a fuss, Alef waited until the first swarm of shrapnel ripped by her head before cocking the rifle and blowing a chest apart. The slaika tumbled noiselessly from its saddle, but the dragoons were too spaced-out for it to hamper any mounts.

Now the shrapnel flew thick and fast. She steered with her thighs, rushing towards the Ispahat, cocking the brim of her akubra and working the lever like a water pump. Heads shattered and arrows went wild. She wasn't in javelin range yet, but when she was the relative slowness of the scuttler might do her a diservice.

There were only eight Ispahat now. A few slaika bodies were visible lying amongst the long grass. The dragoons hung back, less eager, and swerved from side to side. The jerky motion of the scuttler impeded her now that the dragoons were swerving, although it had been less troublesome in the head-on charge. Alef angled towards the north, bending in her seat and hoping that there weren't any burrows or dens.

The scuttler cantered, the thierets pacing it easily. Twisted as she was in her saddle, Alef found it impossible to maintain anything even resembling a level keel. She slung the rifle over a shoulder, faced forward, and put on all steam.

It was a rough run. The recirculator was top notch and the thermal generator kept the boiler hot, but the cistern would not last forever - especially not at this speed.

Javelins started to fall. One shot into the forward left leg and shattered amidst the gears. The leg choked and the entire scuttler almost went over, tripping to a standstill. Alef leant the scuttler back on its rear four and bucked the front legs. The splinters shot out, a sliver embedding itself in her cheek. She winced, glanced over her shoulder, and made note that the drag0ons were almost upon her.

Fuck it, she thought, jamming the gears until the scuttler was in a steep foward crouch, the underbelly - universals and cabling - exposed to the on-coming antagonists. She took the rifle and crouched behind the boiler, drawing a careful bead on the foremost Ispahat and leading by a few feet. It's carapaced chest caved-in and the slaika wheeled its mounted, wheezing bile as it headed back for camp.

Alef sighted again. Protected as she now was, the Ispahat held-off, and it took only a final maiming shot in a lower abdomen for the decimated party to retreat back to camp. The knot of new dragoons heading out to meet them slow to a stop and turned back as well.

Evidently, it had been decided that Alef and her scuttler were not worth the trouble. They would probably track her by night and try and take her in her sleep. Considering the price you could get for a Bielen east of the desert - and the desirability of a closed-system scuttler - it was entirely understandable.

Nonetheless, she put steam on again and decided to rest in shifts.

I'm in one of these eager, oddly-productive and mildly-felonious moods this evening.

29 June, 2005

Le Coup de Grace.

I sat stock still in absolute awe of what had passed. The Caliph glanced at me carefully between moves, obviously anticipating some out-burst.

'What do you intend?' I asked. He chuckled.

'I intend to win,' he said, ' to beat causality. I shall finally be privy to the ultimate nature of the universe.'

'And what,' I asked, 'is that?'

'I have no idea, but now that you are here I may finally play my gambit.'

'But why wait so long for myself, and not another?'

The Caliph replied:

'Have you not been paying attention? I have not been waiting. I brought you here in my flier on the day that I arrived, and now we are setting to work - a witness of some technical knowledge and an old, old man preparing his experiment. Now watch carefully, and should you be lost, you may return to the material by way of prisms.'

And with that, he checkmated infinity.

A twisting miasm of time and space ran through that palace chamber. I felt myself flickering from epoch to epoch, bearing witness to countless dimensions beyond easy comprehension. Universes of dark matter and living planets that opened jaws to try and drag me down. A rent in reality peeled wide and I was sucked through, tumbling to the heart of an endless chasm of darkness.

'Where are you?' I whispered.

The darkness smiled wryly.

When I awoke, I found myself once more atop the glassed-off disc of sand. The glass was pitted and rutted now, and several strange characters had been chiselled into it - all clearly different tongues. It was night, and overhead the stars shone brilliantly, my bed illuminated by a ring of enormous, silvery moons. The light caught the tips of the waves beautifully, and the sound of the breakers began to knit my shattered nerves.

And there you have the thrilling conclusion of our mysterious traveller's tale. She seems to have come through unscathed, but have you? Irregardless, I don't think we'll be hearing any more from this particular cipher. What's that, Jorge? No, you can't have any royalties.

Greedy bastard.

The Warp and Woof

In time the palace proper presented itself. Gone the omnipresent red stone of Khahir, for now only purest blue shone such as I had never before seen. This crystal, crafted as it seemed from light alone, on closer inspection revealed itself to be water hanging suspended in the form of a chamber, fish swimming through its walls of size and nature out of place for more than sixty million years. At the heart of this chamber, upon a throne of gleaming limestone surmounted by trappings of gold, sat a man enshrouded in plain cotton robes bent above a gammon-board.

In time the palace proper presented itself. Gone the omnipresent red stone of Khahir, for now only purest blue shone such as I had never before seen. This crystal, crafted as it seemed from light alone, on closer inspection revealed itself to be water hanging suspended in the form of a chamber, fish swimming through its walls of size and nature out of place for more than sixty million years. At the heart of this chamber, upon a throne of gleaming limestone surmounted by trappings of gold, sat a man enshrouded in plain cotton robes bent above a gammon-board.'Welcome,' spoke the Caliph, his voice high and trilling. At this word the guide melted away and Siloi flowed into the floor.

'Have no concern - mere cyphers born of necessity and whim.'

I wondered at this, a figure who crafted his duppies with what seemed an absolute lack of concern. He wore a smile as I did so, as though he were able to read my thoughts. Of course this was the truth. My mind was as an open book to him. This was the real world, and I had descended from the level of the constructs, this elaborate veneer with which he had covered the universe.

'Not I,' he said. 'That is no construct of mine, the world which you inhabited. And do not be so eager to dismiss it as mere fakery - your universe is neither less important nor less real than this - they are one and the same - the mechanical, the philosophical, and the physical.'

'But your servant...,' I said, 'Even so, it is clear that there is some separation. How else can you explain this impossible realm?'

The Caliph laughed. It was a low, short, comfortable laugh. The figures upon the gammon-board danced under his fingers as he played against some unseen intelligence, and the walls dropped away whilst landscape changed and we drifted through aeons of time to a single stone hut upon the shore of a vast green lake, a lake that in my mind stretched for thousands of kilometers as I watched a figure exit the hut and tend to a flock of something known as goats.

It was the Caliph, old and wizened, his face a mass of creases and his head all but hairless.

'This was I,' he spoke 'founder of the red city of Khahir - a name which at this time still meant something, though it was only 'Home'.'

The old man was a lunatic, a hermit mystic, bent at all times over his scrolls and tomes as he leafed through philosophy and made leaps of illogic that any other would dismiss as pure lunacy - which it was. Upon a cured goat-skin he made notes in charcoal, and observations from over a shoulder revealed complex geometric patterns that wound their way about a single point that all neared, but never quite passed through. One wall, a rough black slate, was the victim of endless chalk missives, erased and repeated in various manners before commitment to the goatskin on the floor.

One day, the old man laughed at his discovery. He was a crippled, shambling mess now, his goats barely cared for. He lived on roots and berries and the milk of those nannies which stayed by his hut out of habit and a nostalgia for better days. But on this morning uncharacteristic animation infused him, and he rose to with glee to set about his work. Taking several figures from a leather bag beneath his pallet, the Caliph laid-out the parchment and, with absolute care and stern concentration, began to move the figures slowly about.

This practice continued for a considerable period of time. After an hour or so of manipulation the figures would complete a complex circuit, and the Caliph - his work seemingly done - would relocate and recommence.

Time wore on - days passed - and slowly the nights ran into day and the old man began to blur, his flesh melting into the aether until a point of light drifted in absolute, encompassing darkness. Still the figures moved.

Lines of light were scored in time by the Caliph's passing. Worlds drifted below and aeons reiterated. Looking once more over his shoulder, I saw the deft gammon of one who has dueled with the universe.

The Caliph descended from the void upon the face of the earth, manipulating, battling with his games until a flier presented itself. It touched down on a spot in the desert where, several years and a moment later, I was to sleep. Still we had not made true contact with what I considered the real world.

'We will be there in moments,' said the Caliph. He smiled at me from his board, and I waited in the flier while he subdued the anxious hordes, bent the history of the city - manipulating the designs of ancient surveyors, architects and kings - until walls stood against the rioters and the flier had ceased to be.

The Caliph turned to me.

'And so I do not control anything. I play against the universe - existing at a point not wholely separate, but far from contained, an objective vantage of which none of this is a part'. He gestured at the palace - it flickered and we sat once more in the ancient stone hut. And inscribed on a sheep-skin were the mercurial formulae - no, formula, for it was all at once, the battle against his pieces - of Ish. People walked between the lines of ink, and I looked down at myself in the heart, contained within a circle that none of the paths ever quite touched.

'They move as I move them,' said the Caliph. 'It is a hard game to play, a difficult instrument to work.' His fingers flickered like insect wings as he worked the populace. 'They cannot be forced in any one direction - only have the way blocked. So I cut the circuits with my pieces, moving ever slowly towards the centre, and in time the streets will guide them all to the correct points, and I, quite possibly, will win.'

This should finish-up next post, although I'm not sure. I may be sucked into my own head before reaching completion.

28 June, 2005

At the Gates of Eternity

It was a long and winding morning in the sunshine of the sea. The streets, narrow and broad, seemed to twist at there own volition. The urchin, named Siloi, attested this to be a common fact, and spoke of times passed when the Caliph first came to power. Riots, he said, and untold civil discord, had wracked Khahir from every quarter.

The Caliph had settled upon the city in a flier made of bronze, and declared his right through the display of various basalt marques which scribes attested the veracity of upon the alter of Revelation. As time passed, and the Caliph sought to reassert this ancient, uncertain dominance, sages and saints upon the altar had denounced him as a false prophet, a sower of dark epochs, and from the altar had risen-up a translucent emerald sprite - this ghoulish, necrous, nacrous fire that enshrouded the soothsayers and consumed them to fine white ashes in refutation of their lies.

Sects had formed, cults of doom-sayers proclaiming the Caliph some dark enchanter from untold realms. That such was a possibility I well knew, and listened as Siloi told of the battles that had raged in the streets, and the fires and famine and riots until the very walls themselves encircled crowds and refused to let them pass.

'And ever since that time, the roadways change endlessly, so that one might walk forever along the same road and never reach its end'.

Thus were the rumours of the nature of Kahir confirmed. The swirling, inconstant map of the formulae of Ish, transcribed in mutable characters upon the very face of the city. Such sorcery was strong beyond any that I had encountered, spawned no doubt of some strange source that I must unearth if my mission were to be successful.

The path we took was a tree-lined avenue, broad and airy with fountains at the heart of crossroads. The sun, hanging away to my right, brought sweat out upon my forehead and left me feel rather tired. Eventually, I hailed a rickshaw, and asked the runner to take us to the palace. He set-off with good speed, and i am sure that he took us several miles before I noted that the sun now appeared hanging on my right.

I looked along the avenue. In the distance were the tips of the palace domes and spires. Some enchantment was afoot and I, far from my laboratories and with my tools despoilt, was forced to bear it as the rickshaw-man continued along the road, the sun turning almost imperceptably overhead.

'It's no good,' I said in time. 'It appears that we will never make it at this rate.' I gave the man his fare and we set-out again by foot. Now Siloi and I made steady progress, the sun having begun to dip with the later hours of the afternoon. The shadows stayed upon my right as the spires slowly rose above the horizon, and after what seemed hours we stood alone amidst an enormous quartz-pathed square.

Over us, looming, was the palace. Siloi murmured something fearful about the emptiness of the place, that the bazaars would never clear so early and that the sun had ceased to fall. I observed this also, and turning I made for the palace gates, a portal of oak sheathed over in gold-leaf and inlaid with platinum.

There were no guards, for a magnate such as this had little need of them. Twin towers of carven stone hung ready to fall over us, shaped in mimicry of the totems of one of the ancient polar tribes. My fist fell towards the panel, but as it did the gates swung wide and before me stood a figure of uncertain features. This shadowed, shifting form, opening its mouth and speaking in a tone that seemed to bipass sound, greeted me in the ancient and near-forgotten tongue of Yar.

'Welcome,' spoke the figure. 'The Caliph awaits you with great eagerness. It has been some time since an individual of purely-intellectual curiosity came to call upon the treasure-hordes of Khahir.'

It beckoned me in, mtioning for Siloi to follow also. We entered a garden of twisting amber paths, and took turns at angles seemingly incorrect, almost impossible, along a gracefull curve that provided a view, when I turned to look, of infinity spread-out across a glittering, star-draped field.

'Not for all, this passage,' spoke the figure. 'Emissaries and emirs, all pass through the gates in the realm above, that which is formed of illusions by my master to provide a shell within which the delicate clockwork of reality might run its couse.'

I took heed of his words. Uncertainty beset me at every turn. It seemed asthough we had entered some prism, a multi-faceted globe, and every turn of feet or head set us tumbling through a portal into another such place, being drawn ever onwards through infinite chambers to a single point of azure light that somehow showed itself above these flickering images of places, times, thought, emotions and matter.

Within the City Walls.

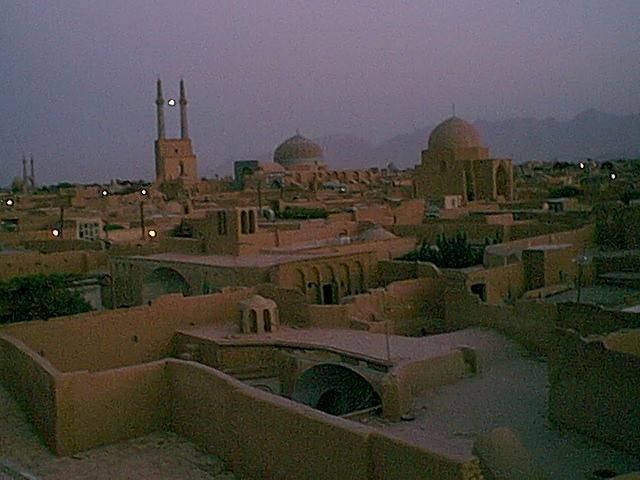

It was a single spark of light that announced that city, the destination which it had been three years' goal to reach. It hunched upon the shores of the Crimson Lake, red stones of kiln-crystal that shone like dry blood at noon. Broad, blocky buildings capped by polished domes, and long, winding streets that scribed the arabesque formulae of the sacred name of Ish. Around the gates a market seethed like ants upon a drop of honey, and through this mass of tents and huts and stalls I pushed my way to the gates, pausing only to purchase a flask of water and some greasey, ill-kept meat.

The creatures at the guardhouse accosted me. Feathered brutes, welding their heavy claws. I paid them a few of the coins which I had secreted before the assault, and was allowed ingress through the keep and into the heart of Khahir.

A dark, dense place. Everywhere the red hung above me as I walked through these strange canyons of sanguine stone. The people paid me little heed, outsiders being common from the west. I pushed through crowds of merchants and traversed desolate squares of academia, noting as I did the curious, twisting, winding nature of the streets. I was footsore, sought a hostel. The interpreter had been one of the first to die, shrapnel from a malfunctioning rifle shattering his skull. I made certain signs common to the Oceanic realms, and by them it came to be understood that I desired a bed.

I slept, I do not know how long I slept. I awoke refreshed but aching, my muscles taught like harp strings and my neck a tangled knot of sinew. Through the window came the cries of the souks, and the stutter and warble of fierkins as they spruked their eggs on the corners. My clothing had been laundered, and the bell-pull conjoured a young boy who provided me with fruit, cheese and an omelette. He offered me his services but I dismissed him, far to preoccupied with my various designs.

It had been three years ago that khahir had first been brought to my attention, a curious settlement raised out of the sands and bedrock of the sea bottom. Word coming from Baiyn and Coenos had spoken of some new caliphate, and in my role as chief advisor on matter of Science and Eldritch lore I had lost no time in absorbing all the information that I could. It soon became apparent that queer magics were astir, and rumours drifted from the plains of roadways that shifted like stirring serpents. I petitioned the Primate at once to be allowed an expedition, but relations were uncertain and my influence doubly-so. I convalesced three years in subterrean laboratories before word came that I might go. A pitiful knot of dishonored guardsmen and merchants formed my company, my designs buried amidst paltry but over-riding responsibilities to cement trade.

The cravan wound its way down from the mountains and shuddered into red upon the lip. I stood at the window watching the maketeers flow by.

In time my mission reasserted itself. I decided upon what to do. I took in hand my pitiful baggage and settled my accounts with the hotelier. From amongst the street urchins I aquired a twisted youth who possessed a smattering of Parvasi, in which I am conversent. We set away up the thoroughfare to the palace of the Caliph.

27 June, 2005

Trekk to Khahir

In the shadow of the dying sun I walked my way towards Khahir, my feet raising clouds of dust that drifted, leaving shadows in the twilight.

In the shadow of the dying sun I walked my way towards Khahir, my feet raising clouds of dust that drifted, leaving shadows in the twilight. My legs were sore and my breath short. I had been walking for seven days, since the Barakesh had fallen upon my caravan a month from Iskapar. Their baron, a mace clutched firm in hand, had loosed a barrage of wracking cries and knocked the Captain's head clean from her neck. Our much-vaunt gunnery amounted to little more than a deafening display when met with scatter-bows from trenches in the embankment.

It is somehow hard to believe that where those travellers fell was once a river. The drop is a hell-hole for travellers, and there will be many more deaths before the Primate finally conceeds to place a garrison on the lip of the Escarpment.

A river, and now I wandered an ancient sea. Outcrops of bedrock, weathered to uncommon smoothness, arched up from the softer sediments and displayed the skeletons of ancient dragons old before time. Lances of metal shot from the plain, unyielding to my knife. On the third day I had come across the glassed-off site of a flier landing. Dust lay thickly upon the cracked disc. I slept there, clutching my pistol in fear of marauders.

On the fifth day, I awoke where I had tumbled with the darkness. The sun, dipping and rising above the horizon, the starless night in this strange latitude left me disoriented and afraid. I found an arcing jut of dun stone rising above me as though ready to fall. Stumbling from its shadow, I had been confronted by some primordial creature, snarling as I lept for my pistol and shot the think through the neck.

It was scaled and dark in complexion, and its flesh tasted rancid and sweet. Yellowed fangs jutted from its jaws, its fins bent and muscular to an amazing extend. Its tail flicked, coiled and uncoiled, even as I butchered it.

And on the seventh day, as the pangs of hunger worried me again, I saw Kharir gleaming on the horizon

26 June, 2005

Mouentaneya Puurh Ley Dheybhuton

The streets east of Mouentaneya are flocking with hosts of Beetles. They sell betel nuts to the passers-by and crouch upon the footpaths, digging their pincers into the sandstone and waiting for the sun. The weather's always hot in Mouentaneya, a combination of scorching, arid days and dense, humid nights. The only reason anyone lives there at all is because of the wells, although few admit it.

Down below the city in coiling hosts of viscosity lies a sea of aldramine, that most rare of rarities born of the encounter between coal, oil, natural gas and sulphur dioxide. All attempts to replicate this concoction in laboratory conditions have led to death by immolation or poisoning. The popular consensus is that the scientists are just making it all up.

And as to this aldramine, and its actual applications, that is an equal mystery which most are disinclined to discuss. The cities out beyond the rim where the Gaarbool live, inhabiting their giant termite mounds and birthing petty monstrosities, are the last point where any human ever sees the aldramine caravans. The drivers are all condemned murderers and priests, working the passage in exchange for a weregild for their families. They never come back from beyond that enormous clay-and-dung wall, and the humped, eggish domes seem to discourage inquiry.

So rumours abound, of course, of some heinous beast beyond the walls, some civilisation reliant upon the consumption of aldramine to facilitate some mysterious method of attaining immortality. Many young idiots have died drinking the noxious brew, and this ironic event has become something of a spectacle in the lower quarters down by the docks. Spectators, voyeurs and miscellaneous degenerates will gather about as some young fool 'takes the challenge', and shoots-down a cup of aldramine (or, as they call it, 'scham'). He'll gibber and chortle for a bit, tear the flesh from his face and legs, and the bets generally run as to whether he'll die of the poison or of blood loss. The coroners and forensic pathologists of the district are notorious for running hand-in-hand with the bookmakers. Tanisson's, most reputable gammon-house in town, refuses steadfastly to take bets. Yolande's, a subsidiary of Tanisson's owned by Ma'am D.T's neice, will give you five-to-one odds on a healthy young buck downing half a quart.

The Beetles love these little get-togethers. They usually eat the left-overs once the autopsy is over, since it's hard to identify who's who when the corpse is missing a face. They'll eat the entrails and drag the remnants over to the Temple of Azothoth, where the high priests are in the habit of giving them sacred betel nuts to sell for gold.

Meydenheddh Briitshd.

I greet you, noble reader, and thank you for your patronage. or matronage. It's entirely your choice. If this is too loose and rambling for you, get out now, while you can. There's plenty more where that came from.

Also, read Doon. Do it now. It's by Ellis Weiner.

Sorry.